Seeing my dad in prison is like seeing a different person. My once powerful father that I looked up to for everything, now dressed in double denim, sometimes shackled and occasionally strip searched. Our visits and phone calls center around his case, the trial, the appeal. Our last family photo of him in his own clothing was taken in early 2000. He has aged significantly since then; we all have. Where there was once a family unit, there’s now four disparate individuals related by blood. I feel like an adult orphan and I blame my father for this. He knows I’m angry with him–for my family’s tenuous situation, his selfishness, and the countless hours spent in jail and prison–but he dismisses my feelings, calling them, in his words, “bitterness.”

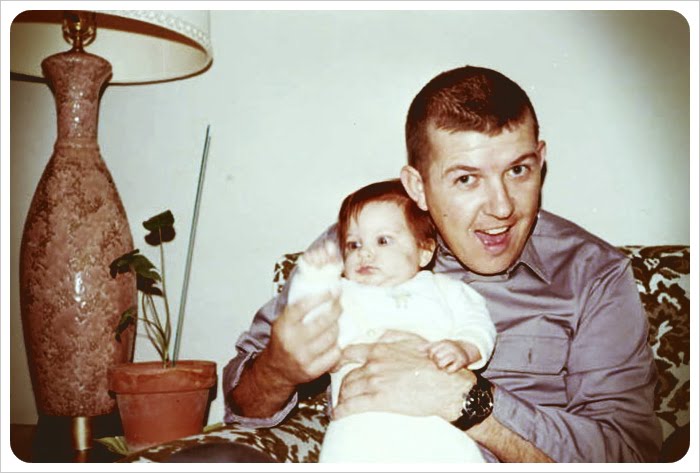

However, having now lived through his eleventh year of incarceration, I realize the importance of remembering and preserving the good times and memories I have with my father before his arrest. Amid the feelings of loss and a lack of control over my life, I do still have a father, and the fact that he’s serving a life sentence doesn’t alter that truth. When I see him now, it’s like seeing a shell of his former self with a new personality; as if he was body snatched and replaced with a clone. In these times of frustration, there’s an ever-present yearning to escape–through travel, through isolation, or by acting on self-destructive impulses. So as a means of self-preservation, it’s essential to occasionally honor and give life to the brighter childhood memories, and remind myself that I’m a daughter, a daughter with a father who loves me.

My parents had carefully worked out their respective roles. If my mother, being a disciplined, health-conscious nurturer, played bad cop by not allowing us to eat sugar cereal, Dad was there to smile, turn a blind eye, and let us gorge ourselves on Fruit Loops. He’d dance around with us in the living room while people picked Juicy Fruit gum off trees in a TV commercial featuring a banjo player singing, “Juicy Fruit’s the flavor lover’s gum!” My sister and I grabbed our dolls as he tucked us in our beds at night and sang us a song, usually Frank Sinatra or Nat King Cole.

One morning after a night of Dad’s Sinatra serenade, my sister and I, about six and eight years old, woke up and noticed the dining room curtains had been drawn. The room was unusually dark, and I thought maybe someone had died. Mom and Dad were drinking coffee at the table and slyly suggested that we open the curtains. I was still groggy and didn’t grasp why they couldn’t pull the curtains themselves. But I did what I was told, ran over and pulled down on the cord as morning light poured into the room, nearly blinding me.

My sister spotted it immediately. “Oh my God, Oh my God! Look look Laurel!” she screamed. I joined her in screaming and jumping up and down, though I wasn’t yet sure why. Dad opened up the sliding glass door, and we took off running outside, like wind up toys in our pink nightgowns. Dad had turned our backyard tree into a Juicy Fruit gum tree, just like the commercial!

Packs of Juicy Fruit were taped to the leaves, and we could only reach those on the lower branches; Mom and Dad lifted us so we could pick the higher packs off too. By the time it was over, I had about five sticks of gum in my mouth and my teeth were covered with that sugary gritty sensation. Mom dutifully collected our packs so we couldn’t eat them all at once, while Dad reveled in our excitement–he was one of us, giddy in celebration of a new, impromptu holiday of his own making.

Every time I see a pack of Juicy Fruit gum now, I’m reminded of the tree, our tree, and I smile. I used to just think about all the gum I scored for a non-Halloween occasion, how happy I was, what a great day I had. Now I think about my Dad, his thoughtfulness and creativity, and his desire to make his children happy. I think about the “behind the scenes” of the Juicy Fruit gum tree: Dad coming home the night before with over fifty packs of gum, putting us to bed, sneaking outside with scotch tape and a step ladder, and taping the packs of gum to the tree, careful not to tape them too high. I imagine it was hard for him to get the tape to stick to the leaves coated with moisture of the nighttime dew. These were not the efforts of the absent dads we so often hear who pass their free time drinking beer and watching football. These were the actions of a man whose derived immense joy from seeing his daughters happy.

Around this same time, I had sent away for Lindsay Wagner’s autograph and had it proudly displayed on my bedroom’s pink walls. I liked to pretend I was The Bionic Woman and jump off the backyard picnic bench in fake slow motion, or fake tear through a whole phone book, with the bionic sound effects–ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch–playing in my head.

One Saturday morning, we sat down to watch Bugs Bunny when a loud static came out of the TV: the cable was out. I thought little of it until it slowly dawned on me that I might miss my show the next day, even though TV Guide had informed me it was a rerun. “Don’t worry, it’ll be back on soon,” said Dad.

The next morning after a sleepless night, I ran to the TV, turned it on and was shocked to see the screen still full of black and white speckles, laughing in my face. Dad saw my look of despair, went over to the neighbors and asked if their cable was out too. “No it’s fine,” I heard from over the fence. He returned into the TV den, took off the back of the TV and saw that one of the cathode ray tubes had blown. I had a sobbing meltdown. Dad felt so bad for me, his own eyes had tears as he held my face in his hands, “It’ll be okay.” He removed the blown tube, and off we went to the hardware store.

My future was in his hands. The technician gave us the replacement tube, and I was ecstatic until Dad went to replace it, and it didn’t fit our TV. He began cursing and I had what at the time I would have called a psychotic breakdown, but what I would now more accurately identify as a tantrum. I had to go outside and swing on the swing set to get my mind off of this catastrophe.

We drove back to the hardware store in silence and the guy didn’t promise anything but gave Dad a couple of different tubes to try. I looked at the clock; my heart sank. I could hear the minutes ticking like time bombs. I watched him on his hands and knees, working diligently on our TV while I held my breathe and bit my lip. “I love you Daddy,” I’d say in support. Dad turned the TV on and off to see if what he had jimmied worked, but it didn’t, and I resolved myself to having a non-Bionic Woman evening. As a back up, Dad asked the neighbors if I could watch Jaime Sommers on their TV, but they were watching football instead. I hated them.

Then, with only minutes to spare, Dad turned the TV on one more time and on came a clear, color picture with sound. I ran to Dad, jumping up and down and squeezing him. Mom came into the TV den, “Good job, Michael!” as Dad wiped the grease off his hands with a rag. I sat down on the couch to watch the rerun I had already seen, beaming ear to ear, Holly Hobbie at my side. In my mind, I was relieved knowing I would once again see The Bionic Woman simultaneously with all the other fans as she conquered the world. But now I see how important it was to my dad that I was happy and that he did everything he could for me.

After The Bionic Woman show ended on TV, I had extra time to kill and told Dad that I wanted to learn how to drive. It was time: I was ten years old after all. Growing up, he had let me sit on his lap behind the wheel as he drove down the block. I had tasted blood, and I wanted more.

We had a dark blue Subaru Brat truck complete with plastic seats in the back cargo. It seemed less like a car and more like a life-sized Tonka truck, so it made me feel more comfortable to learn on. But Dad liked it because it was a stick, which he insisted I learn first, because, in his words, “Women never learn how to drive a stick.” He never let me learn the easy way.

One night after dinner, we hopped in the Brat, and Dad explained how to shift gears, “You listen to the engine, and when it sounds like it’s ready, release your left foot and shift up to the next gear. You’ll be able to feel it. The car will chug if it’s not in the right gear,” and he demonstrated the chug as our heads bobbled back and forth in our seats. He had called my bluff and talked to me like an adult. I was deathly frightened and didn’t want to fail.

He drove to my elementary school at the end of the cul-de-sac and told me to switch seats with him. My heart raced as I pushed my right foot on the gas pedal and immediately stalled the truck. He laughed, “Start it up again.” After several failed attempts, Dad laughing like a hyena all the while, I successfully drove the Brat up the driveway to my school, and incline which, at the time, seemed as steep as the Matterhorn. Dad beamed with pride, and I felt such a sense of accomplishment. I didn’t need school. Dad let me drive back home the long ride home and even though the Brat chugged a tad, I never stalled once.

I remember that night so well – turns out the Matterhorn was barely larger than a speed bump, and the long ride home was about five blocks. When I turned sixteen, I got 100% on my driver’s test. I’ve never gotten a ticket, and my only accident was caused when an elderly woman ran a stop sign and t-boned my car from the side. I remember all the driving tips my dad gave me as a little girl and put them in practice every time I drive to visit him in prison.

These are the memories I recount with him every Father’s Day when he calls from prison. When there is a long silence on the phone, and I can’t stand to hear about another cellmate drama, I ask him to tell me another story about my childhood. He has an amazing memory, and I think it’s good for him too; to allow his mind to drift from the bleak reality of his current situation and remember that he’s also a great father who raised two daughters who love him and look up to him. He laughs with me, “You were such a cute kid.”

These memories are the refuge I turn to when I’m full of rage about his life sentence, my mother’s loneliness, our broken family. I revisit the Juicy Fruit gum tree, The Bionic Woman and climbing the Matterhorn in the Subaru Brat, and I remember that it’s all going to be okay.

<3 Ya Woodsy!

i confess this one got me a little teary. Totally bittersweet.

great stories! love them!

Brilliant!

love it laurel…very sweet.

this is fabulous!!

Always seeing the silver lining. An inspiration to the rest of us!

I too, got teary…you definitely have a gift..one you may never have realized if not for how life took this difficult turn…must be amazing therapy.

Wonderfully touching. Loving you from this side of the pond baby cxxxx

Very touching and beautiful story…thank you for sharing.

Woods- you nailed it! For any (and all) of us that have ‘lost’ a loved one – remembering them is the final way to keep them alive.

great story laurel. ur dad had some simple creative ways 2 have fun. he put the same effort to fix the tv as he did the toilet on the house boat. memories r something that will live 4ever. i so miss my dad.

Tears in my eyes just like when I wrote the message about the verdict. Loved the photo, and so beautifully told. Hard to believe it’s been 11 years.

What a poignant narrative, Laurel. I relate to the Bionic Woman story! ch-ch-ch-ch-ch. You have a powerful way with words.

Very touching. I like the way you concentrate on staying positive through such a hard time…

Yoda couldn’t have said it better. Sending you a big hug.

And I am crying. That was beautiful Laurel.

This story is so well crafted in how it effectively “holds our hands” through childhood, into adulthood, and back again. You can’t, and perhaps should not, separate the two… Laurel Woods has done such a great job in her recounting, that we embrace her reminiscing as if it were our very own, and we marvel at her positive perspective on matters – past, present and into the future. The bookend photos, from point A to point B, bring it all “home.” Great story. Great writer. Thank you, Laurel.

Heard you on KCRW 89.9FM “Unfictional” today. You were great. Very interesting to hear the way your family was affected by your father’s conviction. It must have been terrible while the trial went on. Part of you must have hoped it was all a mistake, while another part has to come to terms with it. I guess you story gave me a new perspective on how broad the category “victims of crime” can be.

What wonderful memories- so well told!

This was excellent. It truly represents why it is important to remember the good times and appreciate what you have even if it isn’t how it was. Thank you so much for sharing. Got me a little teary.

You had me at the Juicy fruit tree! I love you Woodsy! Genius!

Wonderful, bittersweet description of the kind of love that endures even when you don’t think it should; even when you don’t want it to. I totally get it.

Laurel, this is amazing! Sorry it’s taken me until now to read it. Great job! I’m off to listen to you on KCRW next!

Wow. So moving to hear your perspective.

Thank you for sharing. So wonderfully told! xx